„On C2PA“

Dieser Artikel arbeitet (optimistisch) die (gravierenden) Einschränkungen für das „Foto-Echtheitssiegel“ – die Content Authenticity Initiative – heraus.

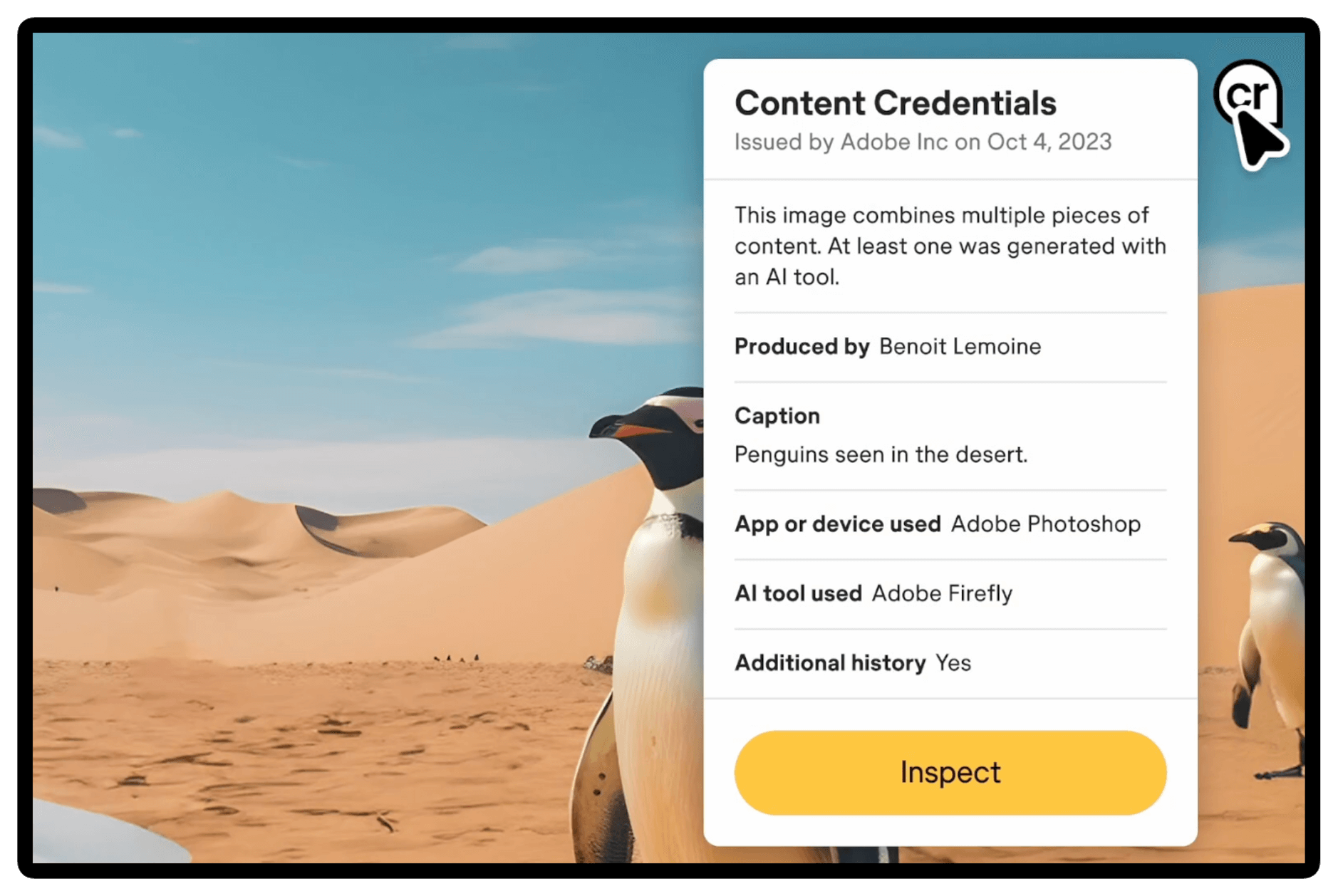

When you take a picture, the camera makes a little data package called a “manifest”, which records a bunch of useful stuff like the time, the camera serial number, the name of the person who owns the camera, and so on. Then it runs a bunch of math over the private key and manifest data and the image pixels to produce a little binary blob called the “signature”; the process is called “signing”. The manifest and the signature are stored inside the metadata (called “EXIF”) that every digital photo has.

Then, you share the public key with the world. Email it to your colleagues. Publish it on your website. Whatever. And anyone who gets your picture can run a bunch of math over the public key and manifest and pixels, and verify that those pixels and that manifest were in fact signed by the private key corresponding to the public key the photographer shared.

Praxis beißt jedoch oft die Theorie. Für wie legitim nimmt die breite Bevölkerung digitale Echtheitsattribute von Fotos ohne größere Verbreitung wahr? Solange die Smartphone-Kamera-Apps von Apple, Google und Co. nicht mitspielen, bleibt es ohnehin eine theoretische Diskussion.

Publikationen sind natürlich trotzdem verpflichtet, ihre Informationen zu überprüfen – neben Bildern sind das etwa (Augenzeugen-)Aussagen und (Audio-)Beschreibungen.

Die Vorstellung zeitlich mit Fake News zu konkurrieren, weil man potenziell Fotos flotter auf ihre Echtheit überprüft, erscheint mir als ein Wettrennen, das man nicht antreten sollte. Vielmehr müssten die Werkzeuge von Content-Schaffenden auf die Gesamtqualität der Berichterstattung ausgerichtet sein.

Adobe steht federführend hinter der Initiative, verkauft aber auch gleichzeitig KI-generierte Inhalte, die bereits für Desinformationskampagnen verwendet werden.